Stepping into the Future

Microsoft on the Map, Chapter 1

Introduction

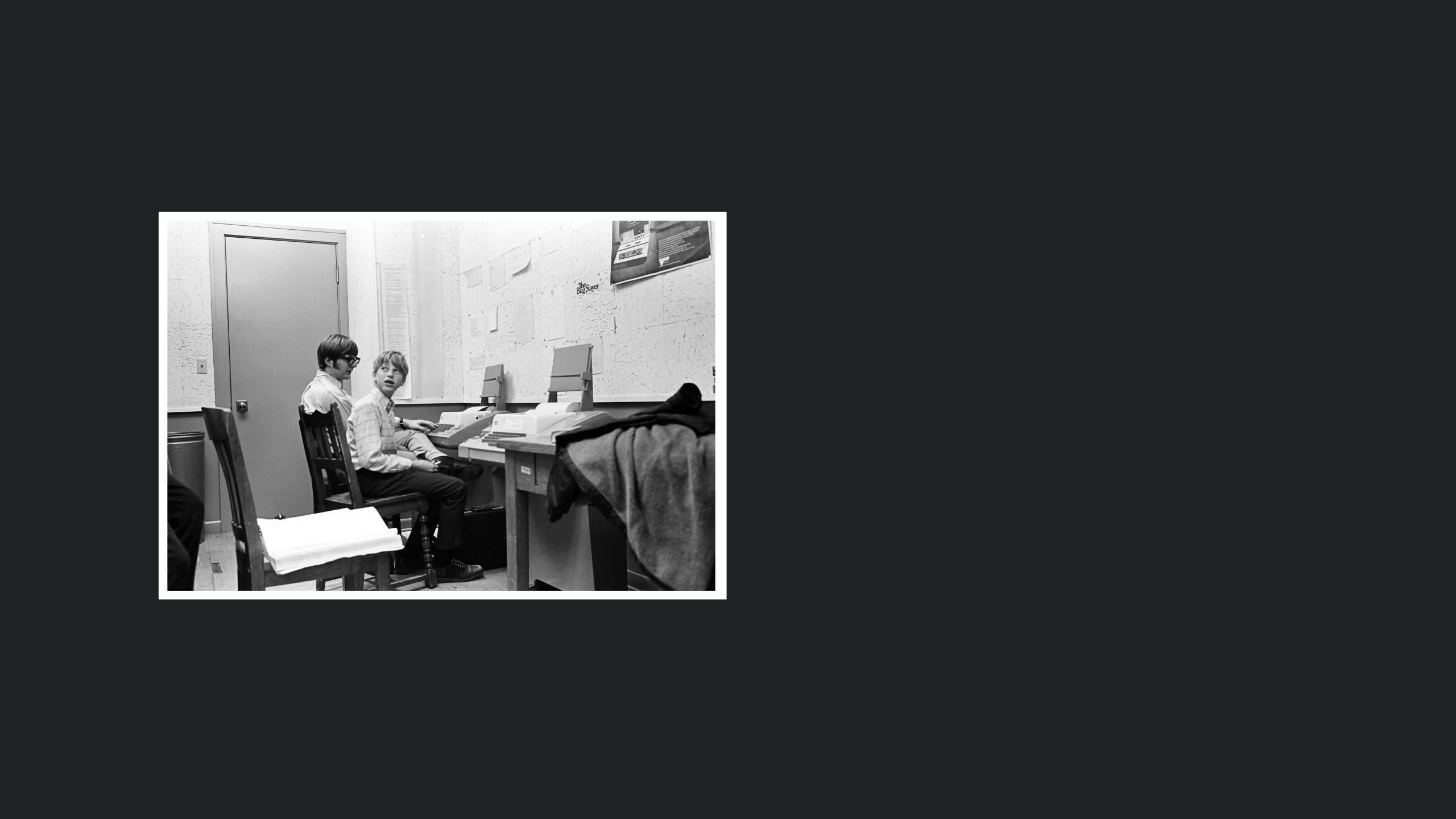

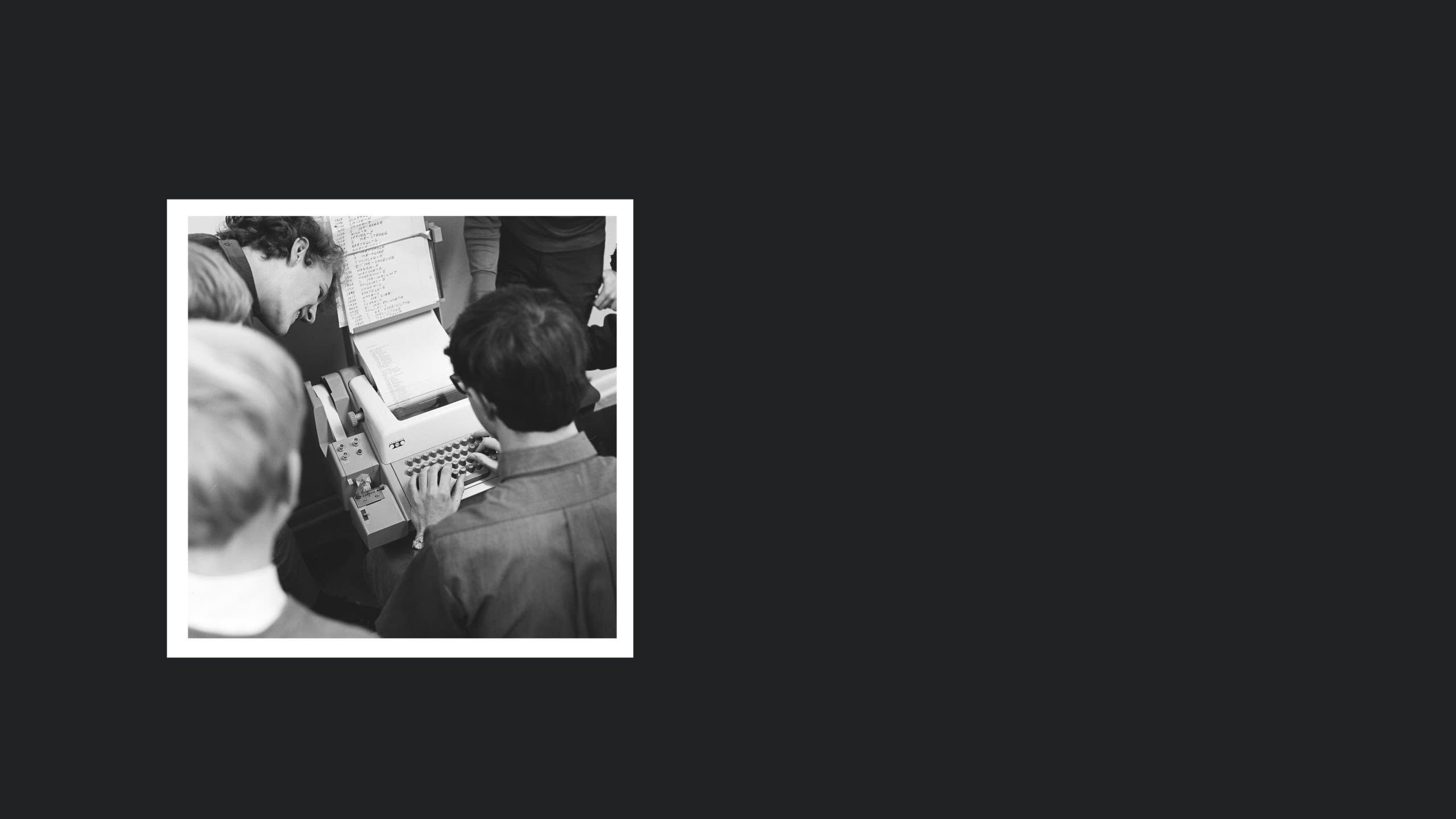

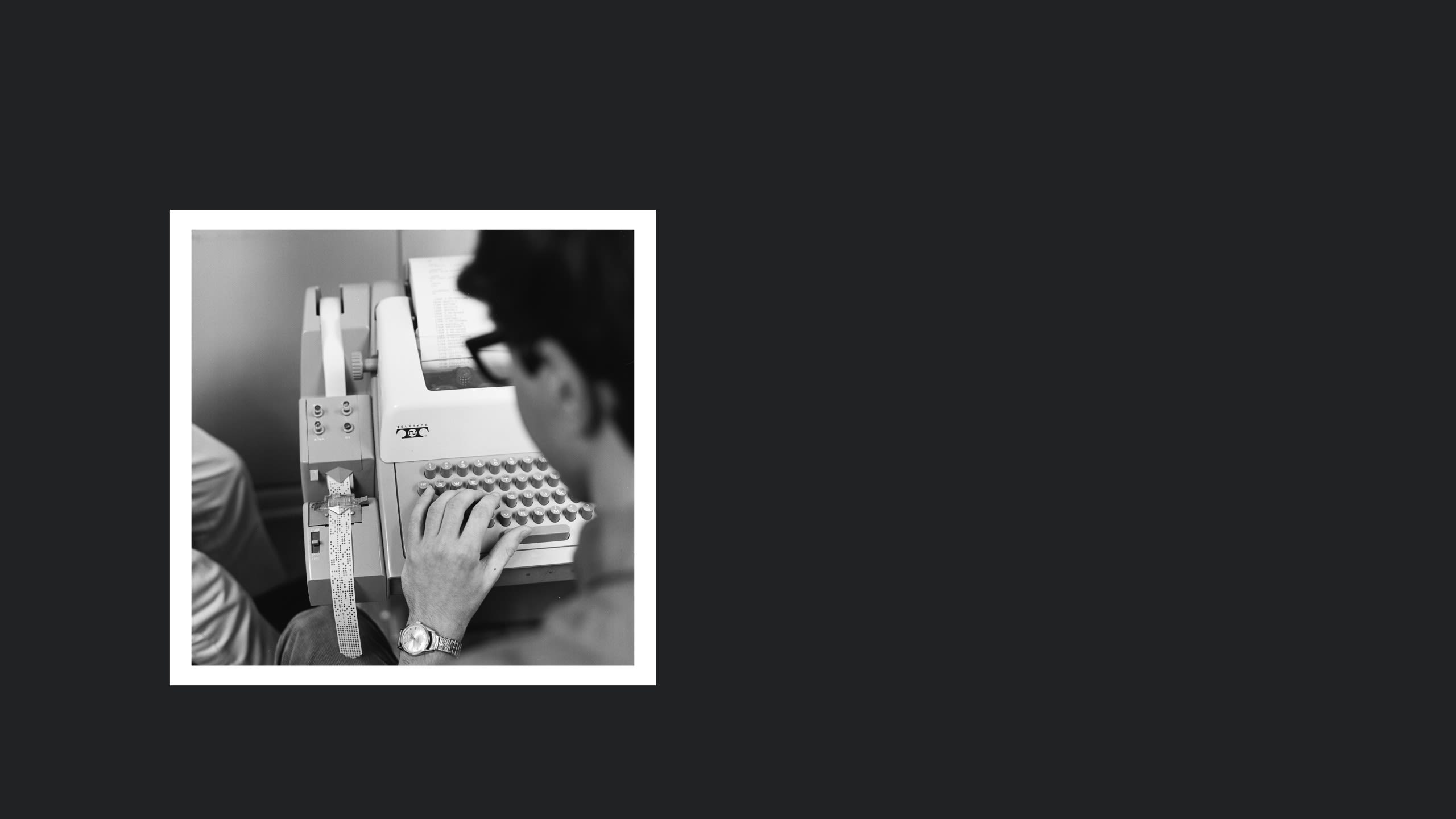

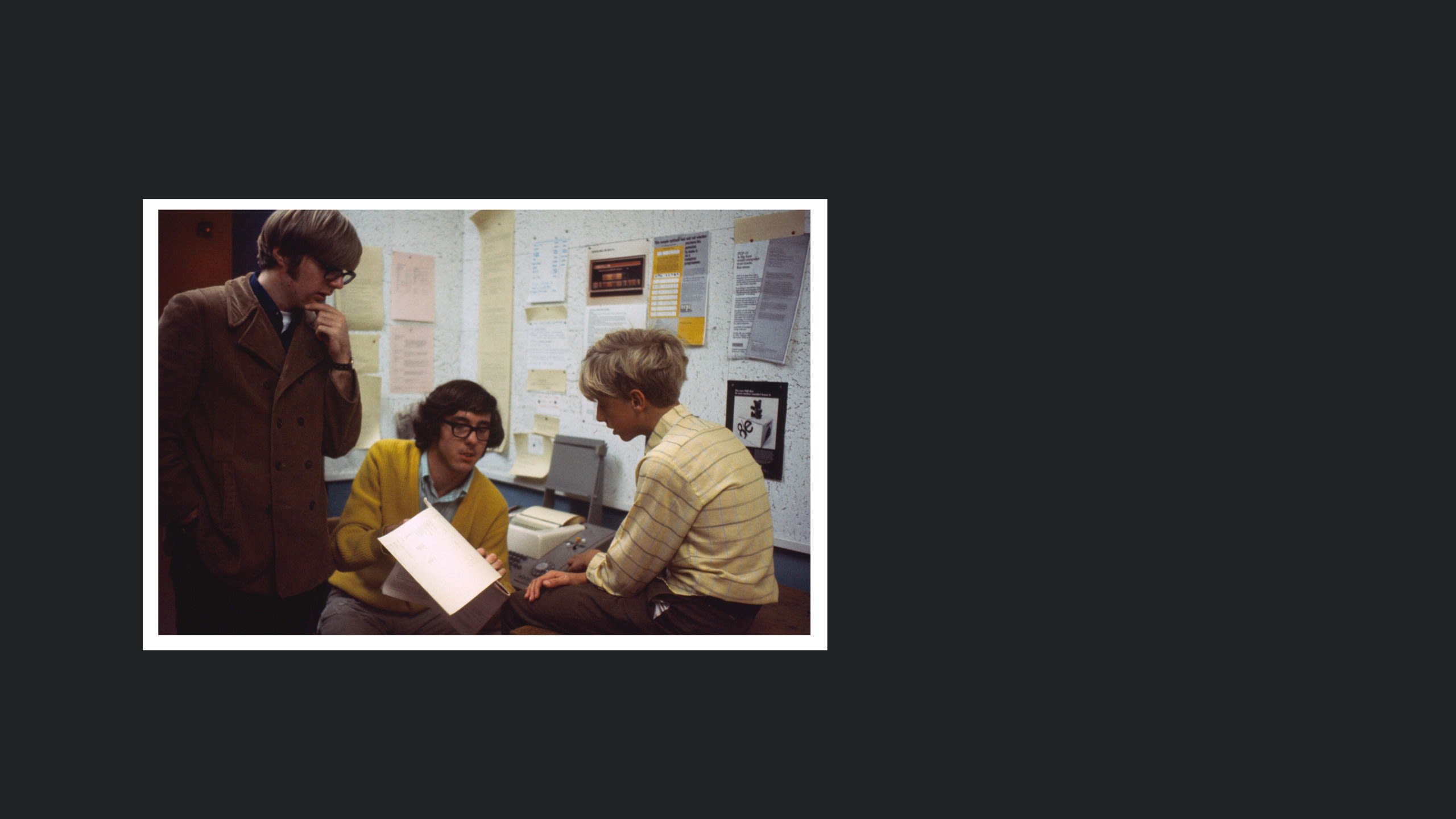

Paul Allen (Left), Ric Weiland (Center), and Bill Gates (Right), at the Lakeside Programming Group. Photo by Bruce R. Burgess, Lakeside School Archives.

Paul Allen (Left), Ric Weiland (Center), and Bill Gates (Right), at the Lakeside Programming Group. Photo by Bruce R. Burgess, Lakeside School Archives.

Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and Ric Weiland, living in the affluent residential neighborhood of Denny-Blaine, grew up in a Seattle where many were infatuated with the promise of the space age.

As children in the 1950s and teenagers in the 1960s, they were surrounded by high-tech industries, a growing university, the future-scape of the World’s Fair, and unique chances and opportunities not available to everybody to use newly developing computers.

Long before founding Microsoft, their experience of Seattle, and what it had to offer them set them on a path to the future.

High-Tech Seattle

The Seattle region was dotted with places where a high-tech future was already unfolding. These industries and institutions were a foundation for Microsoft and other computer-focused companies.

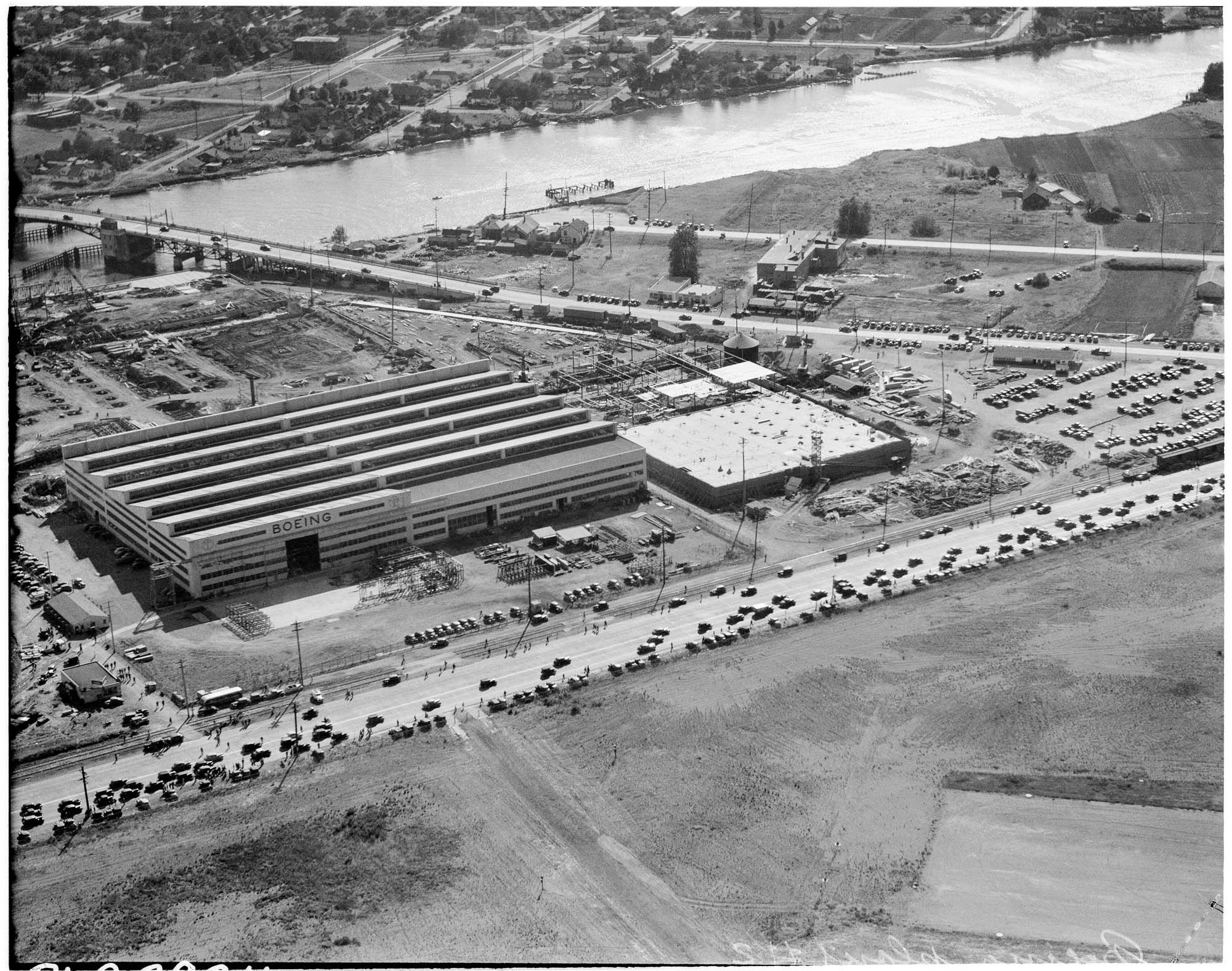

Boeing

Founded in 1916, Boeing helped put Seattle on the map as a hub for high-tech innovation.

As aviation took off, Boeing grew alongside the U.S. Air Force, commercial air travel, Cold War rocket programs, and the Space Race. By the mid-1960s, it employed over 100,000 people in the region.

Boeing, built on Seattle’s working-class roots in lumber, shipbuilding, and maritime trade, relied on a strong local workforce.

The company’s complex projects attracted people from all over the country and the world, including thousands of Black workers who moved to Seattle during World War II.

With Boeing at its core, the city became known for its technical expertise.

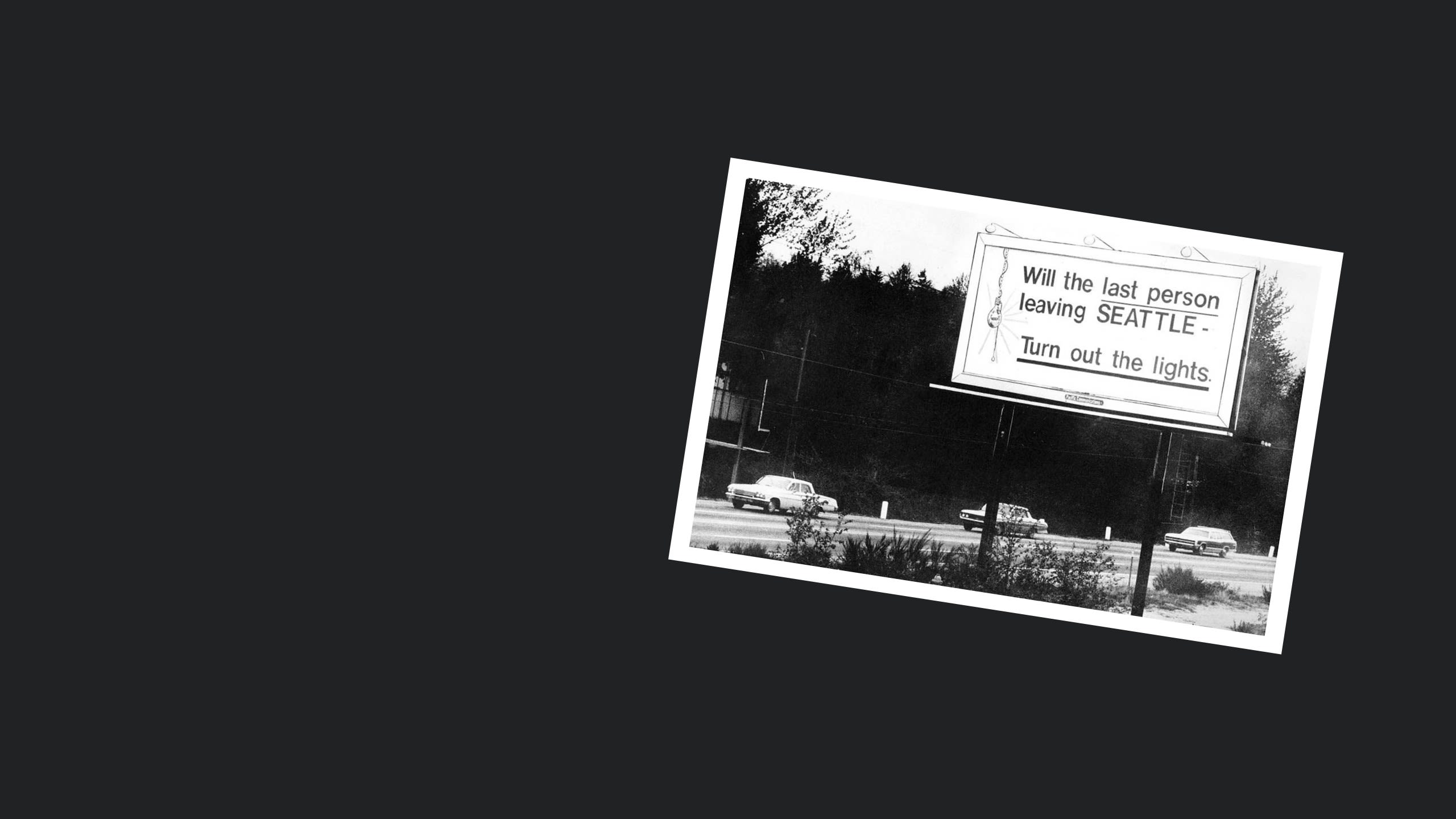

Even tough times pushed innovation forward.

During the “Boeing Bust” of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the company laid off more than 60% of its workers, causing major unemployment. But many former employees took their skills elsewhere, launching new businesses and spreading technical knowledge throughout the region.

Boeing was ahead of the curve when it came to technology, using computers in aircraft design as early as the 1950s. In the 1960s, it brought its computer operations together under Boeing Computer Services (BCS), introducing the latest computing advancements to the region. This influence helped pave the way for Seattle’s booming tech industry.

Boeing also played an indirect role in shaping the future of computing. Several teachers at Lakeside School, where Bill Gates and Paul Allen were students, were former Boeing engineers. Their technical background helped spark the students’ early interest in computers.

Boeing was just one part of a larger ecosystem.

University of Washington

Aerial view of University of Washington campus, looking southwest, Seattle, 1948. MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 1986.5.15719.2.

Aerial view of University of Washington campus, looking southwest, Seattle, 1948. MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 1986.5.15719.2.

The University of Washington (UW) played a major role in shaping Seattle’s early tech industry. Founded in 1861, it is the oldest state-supported university on the West Coast. Over the 20th century, UW grew from a regional college into a leading public research institution.

The university attracted talented people from around the world, bringing fresh ideas and expertise to the region. Its research labs helped advance many industries, while its students filled key roles in Seattle’s growing tech sector.

UW was also an early leader in computer research, quickly developing some of the best computing facilities in the country. As high school students, Bill Gates and Paul Allen gained programming experience on computers either at UW or through connections to the university.

Health science research was another keystone of Seattle’s early high-tech development.

Physio-Control

Lifepak 33 D.C. Pulse Defibrillator Cardioscope from Physio-Control, Inc., 1968. MOHAI, 1991.23, Gift of Physio-Control Corporation.

Lifepak 33 D.C. Pulse Defibrillator Cardioscope from Physio-Control, Inc., 1968. MOHAI, 1991.23, Gift of Physio-Control Corporation.

Smaller biomedicine companies, like Physio-Control, were also important.

Physio-Control was founded by Dr. Karl William Edmark, a heart surgeon who had performed the first open heart surgery in the Pacific Northwest. Edmark invented the defibrillator, a device that used an electric shock to restore a normal heart beat. He started Physio-Control to develop, manufacture, and market this life-saving device that is now found around the world.

Edmark was friends with the Gates family and became a role model for young Bill Gates, who was inspired by the surgeon’s combination of technical knowledge, cutting edge development, and business drive.

Despite its high-tech growth, many still saw Seattle as a tough frontier town. City leaders wanted to showcase how the city was stepping into the future.

And so they planned...

Model of fairgrounds, Seattle World's Fair, circa 1961. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.6.1.

Model of fairgrounds, Seattle World's Fair, circa 1961. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.6.1.

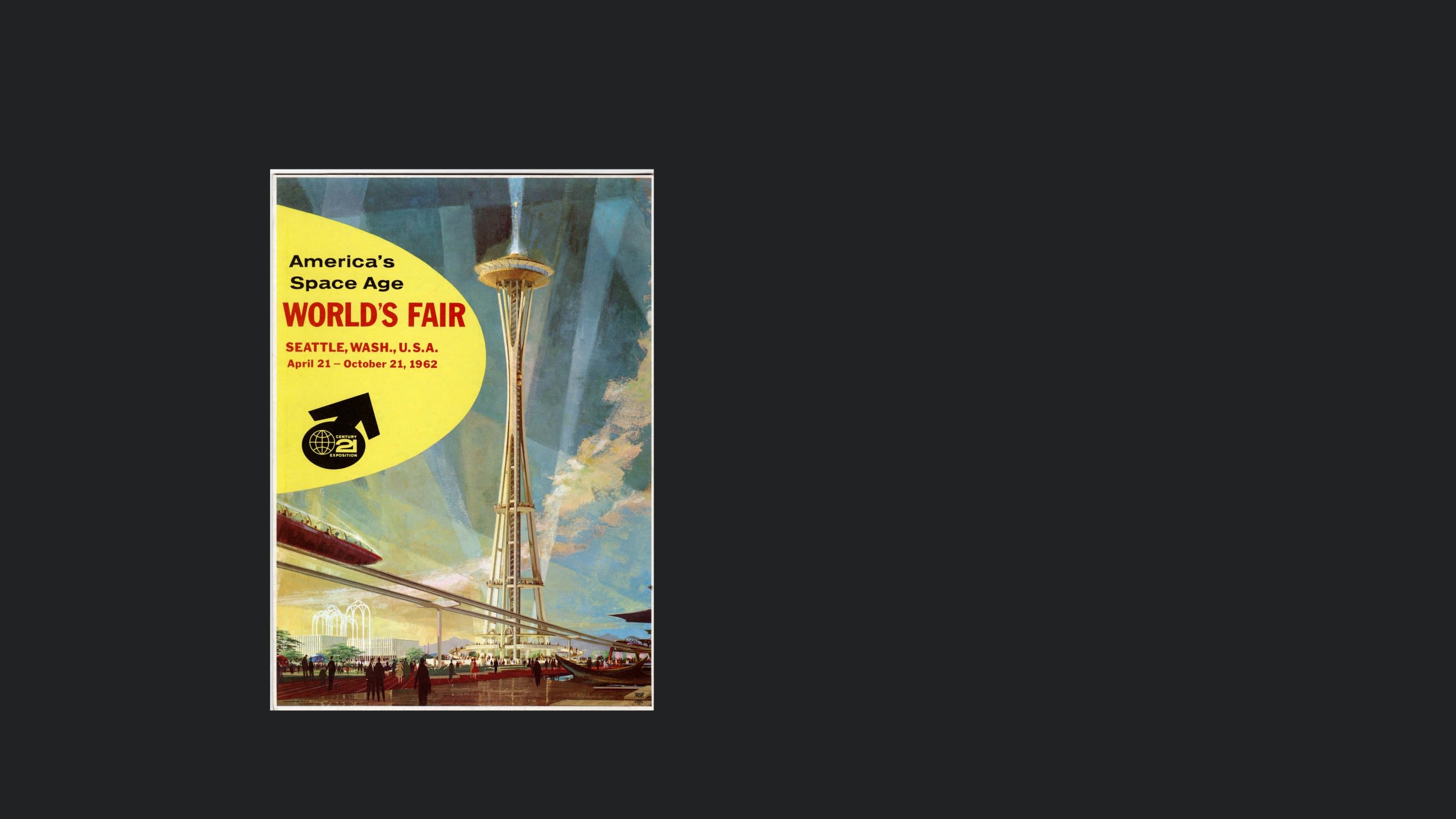

...the Century 21 World's Fair.

The World of Tomorrow

"The 1962 World's Fair in Seattle was all about progress and innovation, and even at the age of six, I was fascinated by the possibilities of the future."

-Bill Gates, Source Code: My Beginnings. Knopf, 2025.

For six months in 1962, visitors to Seattle’s Century 21 Exposition were invited to step into a vision of the next century. Created in the shadow of the Cold War and launch of the Russian Sputnik satellite, the fair’s developers wanted to highlight the promise of U.S. science and industry.

The fair was not always welcoming to everyone.

A working-class immigrant neighborhood was torn down to make space for it.

In addition, most of the organizers and exhibitors were white, which stood out to visitors from other parts of the world. The fair’s vision of the future highlighted advances made by companies for middle-class white Americans.

Even so, the images of the future presented at the fair drew many visitors.

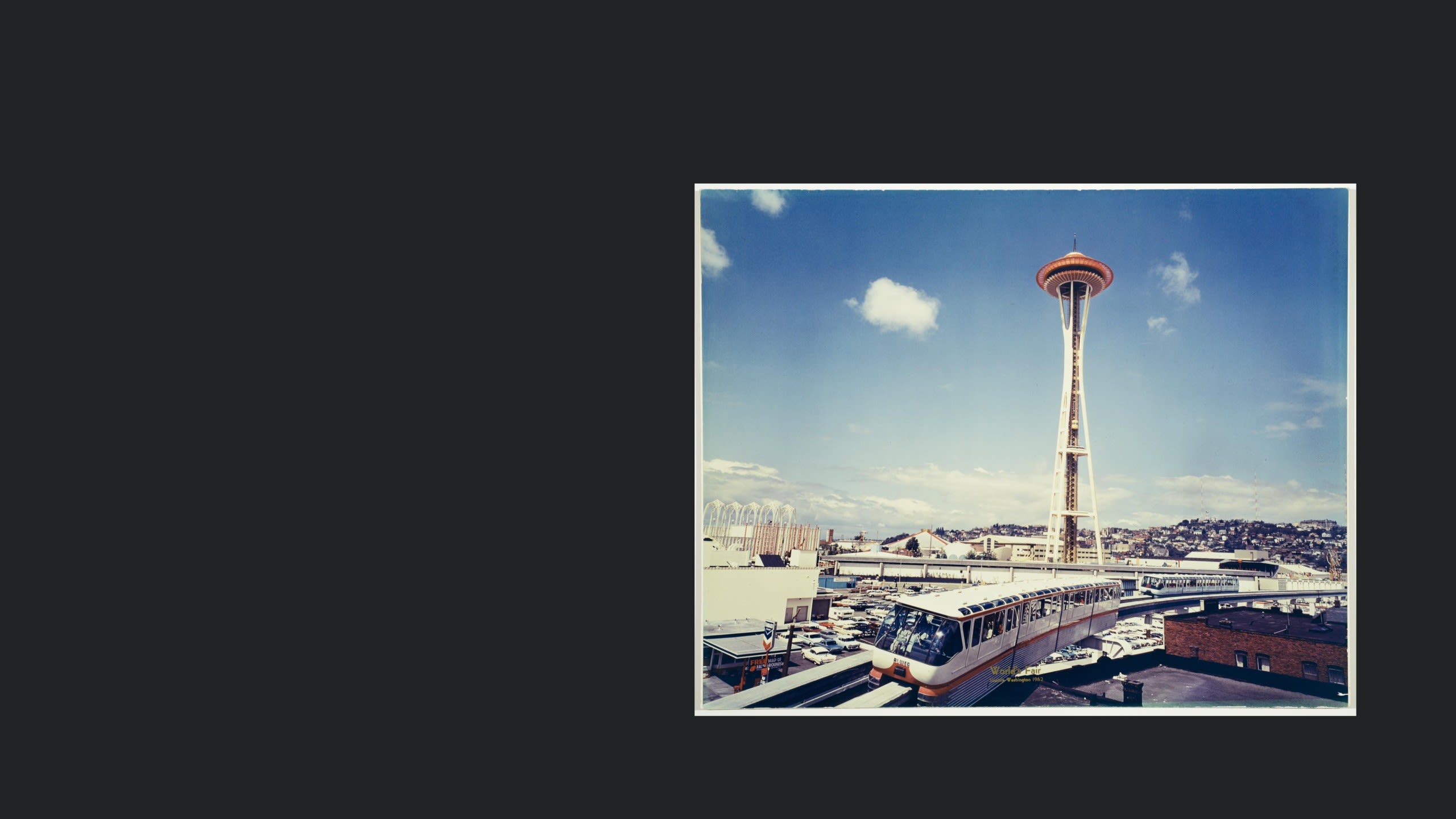

Nearly 10 million people visited the fair, and Seattle became associated with its space age vision.

The Space Needle and Monorail, both still icons of the city, were created for the fair.

The fairgrounds were packed with exhibits that touted the possibilities of technology.

Visitors' Guide to Fairground, layout for printing, 1962. MOHAI, 1968.4505.6.

In the World of Tomorrow exhibit, visitors stepped into a bubble-shaped elevator to tour a honeycomb of cubes filled with visions of the home and office of the future.

Coliseum interior showing Bubbleator, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.11.9.

Coliseum interior showing Bubbleator, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.11.9.

In the same building, the American Library Association exhibit featured a working UNIVAC computer.

UNIVAC computer in American Library Association exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.15.32.

UNIVAC computer in American Library Association exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.15.32.

The nearby NASA Space Exhibit highlighted the latest advances in space flight and included a replica of the Mercury space capsule.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.27.8.17.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.27.8.17.

NASA exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.14.19.

NASA exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.14.19.

The Federal Science Pavilion featured many exhibits about the wonders of science and technology. It included a maze, created by IBM, that simulated an electron's journey through a computer circuit.

Child in maze at IBM exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.25.60, photo by Leigh Wiener.

Child in maze at IBM exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.25.60, photo by Leigh Wiener.

An IBM 1620 data processing machine was on display in at the IBM Pavilion.

IBM 1620 data processing machine on display, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.25.37.

IBM 1620 data processing machine on display, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.25.37.

"We Live by the Numbers," IBM Pavilion postcard, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Seattle World's Fair Century 21 Ephemera Collection, 2021.31.4.

"We Live by the Numbers," IBM Pavilion postcard, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Seattle World's Fair Century 21 Ephemera Collection, 2021.31.4.

There were computer-based exhibits scattered through other buildings as well.

Game at the United Air Lines exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.15.27.

Game at the United Air Lines exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, 1962. MOHAI, Walter Straley Century 21 Exposition Photograph Collection, 1965.3598.15.27.

In each, a gleaming future based on specific worldview of technological advancement as a wholly positive concept was presented against the backdrop of the threat of the Cold War.

Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and Ric Weiland each visited the fair as children and the images of a technology-enabled future framed as a progressive way forward stuck with them.

Paul Allen later credited the fair with sparking his interest in computers.

Computer Time

“It was incredibly rare back then for teenagers to have access to a computer in any form… Soon our small group would have the rarest of gifts: free access to one of the most powerful computers available.”

-Bill Gates, Source Code: My Beginnings. Knopf, 2025.

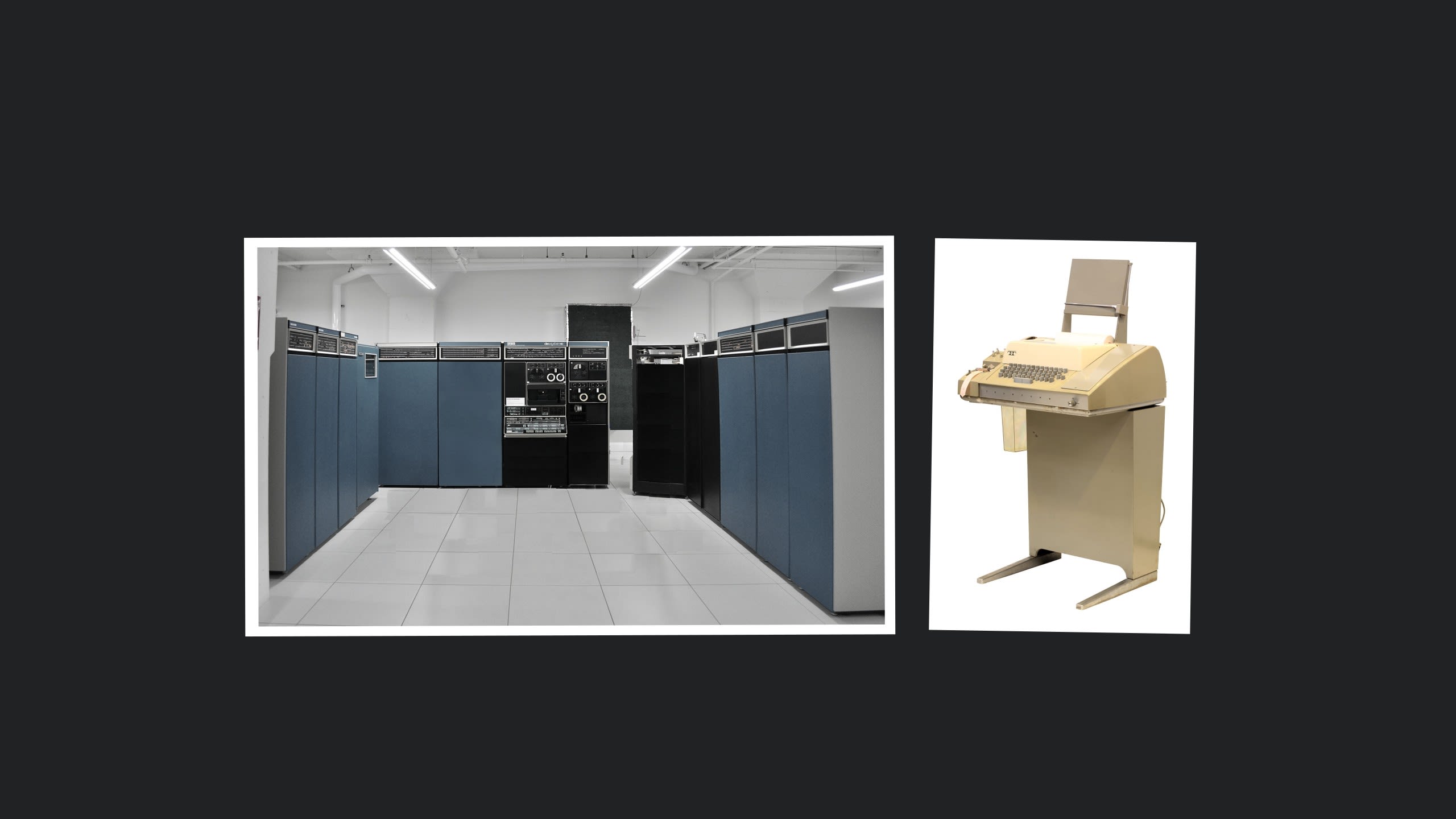

In the late 1960s, computers were massive, expensive machines—far too costly for most schools.

Yet, as high school students, Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and Ric Weiland had unprecedented access to computer time.

Many of the computers Gates, Allen, and Weiland had access to were PDP-10s, like the one pictured on the left, made by Digital Equipment Corporation. They accessed the computers using teletype machines like the one pictured here on the right.

DEC PDP-10 mainframe computer system, 1970s Wikipedia. A Teletype printer. Wikipedia.

Lakeside School

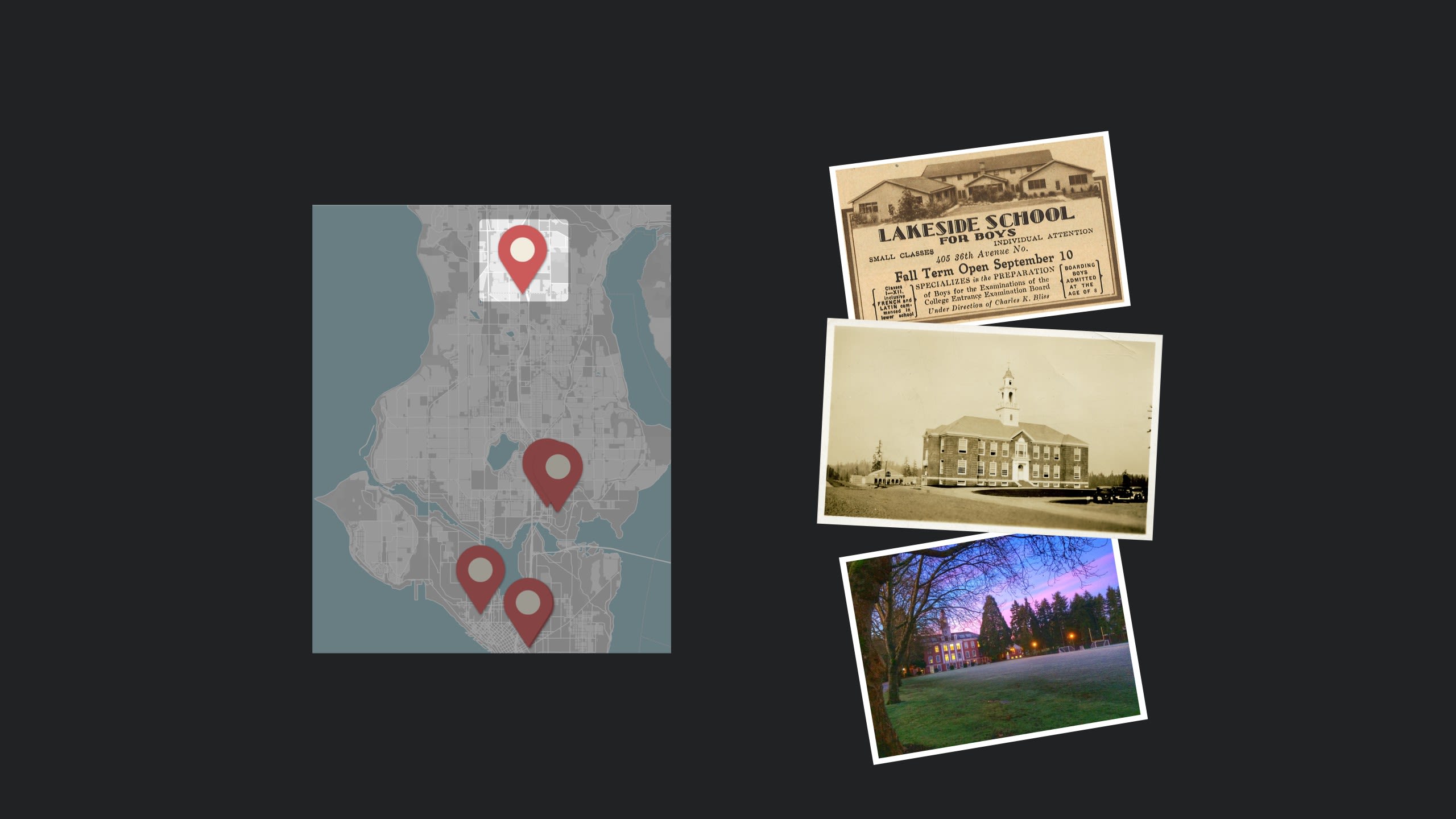

Gates, Allen, and Weiland met as students at Lakeside School.

Lakeside School was a private high school first founded in the 1920s. By the 1960s, it was known as a traditional school for Seattle’s elite families. The school was beginning to change during the time Gates, Allen, and Weiland attended. The first Black students enrolled in 1965. The dress code was made more informal in 1969. In 1971, Lakeside merged with St. Nicholas School, a private girls' school, and became co-ed.

Despite its traditional reputation, the school encouraged independent learning.

In 1968, Lakeside’s math teacher, Bill Dougall, recognized the potential of computers in education. With funds raised by the school's Mother’s Club, the school leased a teletype machine and purchased computer time at high cost of $8 per hour.

Gates, Allen, Weiland, and their friend Kent Evans were immediately hooked, spending every available moment programming. When the school’s computer budget ran out, another stroke of luck kept them going.

Gates carpooled with Monique Rona, deputy director of the University of Washington’s computer lab and co-founder of the Computer Center Corporation (CCC). She offered the students unlimited computer access in exchange for helping find software bugs.

Over the next few years, the students—calling themselves the Lakeside Programming Group—found creative ways to continue coding.

They took on real-world projects, including writing scheduling software for Lakeside and computerizing traffic data collection. They even lived in southern Washington for several months, while they worked on software for the Bonneville Power Authority.

By the time they graduated, they had logged more programming hours than almost anyone else their age.

Lakeside’s unique mix of privilege, forward-thinking educators, and access to cutting-edge technology gave these students a head start few others had.

Leaving Home

After high school, Gates, Allen, and Weiland left Seattle, heading to different parts of the country.

Allen went to Washington State University, Weiland went to Stanford, and Gates went to Harvard.

At Harvard, Gates spent most of his time at the Aiken Computer Lab, where he found a PDP-10 and lax rules for usage. Meanwhile, Allen left school and moved to Cambridge for a job at Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), the company that made the PDP-10.

Soon the two were spending all their available time in the Aiken lab.

In 1974, Allen saw a magazine with a cover article about the Altair 8800, an affordable kit computer. He took the magazine directly to Gates.

"This is it," he said, referring to the beginning of a home computer revolution.

Altair 8800 on cover of Popular Electronics magazine. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum.

Altair 8800 on cover of Popular Electronics magazine. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum.

Altair 8800. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum.

Altair 8800. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum.

They decided that they wanted to be the first to write software for the new computer: a version of the BASIC computer language. They worked around the clock, simulating the Altair on Harvard’s PDP-10.

Soon they had a working prototype and signed a deal with MITS, the company that made the Altair computer.

First BASIC interpreter written for the MITS Altair. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum.

First BASIC interpreter written for the MITS Altair. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum.

A few months later Gates and Allen moved to Albuquerque, where MITS was located and founded Microsoft. Ric Weiland joined them in New Mexico and they began creating versions of BASIC for the many microcomputers that appeared on the market.

Bill Gates and Paul Allen, 1975. Microsoft Archives.

Bill Gates and Paul Allen, 1975. Microsoft Archives.

Soon the young company hired more employees.

Microsoft’s founding employees gather for a portrait. Microsoft Archives.

Microsoft’s founding employees gather for a portrait. Microsoft Archives.

By 1979, Microsoft no longer needed to stay near the MITS headquarters.

They chose to move back to the Seattle area, where a growing tech scene offered a strong foundation for the company's expansion.

Credits

This online exhibit was created by the Museum of History & Industry. It was curated and developed by Dave Unger in collaboration with museum staff.

Images are provided by the Museum of History & Industry, the Lakeside School, the University of Washington, Stanford University, and the Computer Museum.

For more information about MOHAI’s collections items, including rights and reproductions, see the museum’s collections and research page or click on the item link in the caption of a specific item.